NGUYEN, Diane Severin; BEN SALAH, Myriam (ed.); MOHEBBI, Sohrab (ed.)

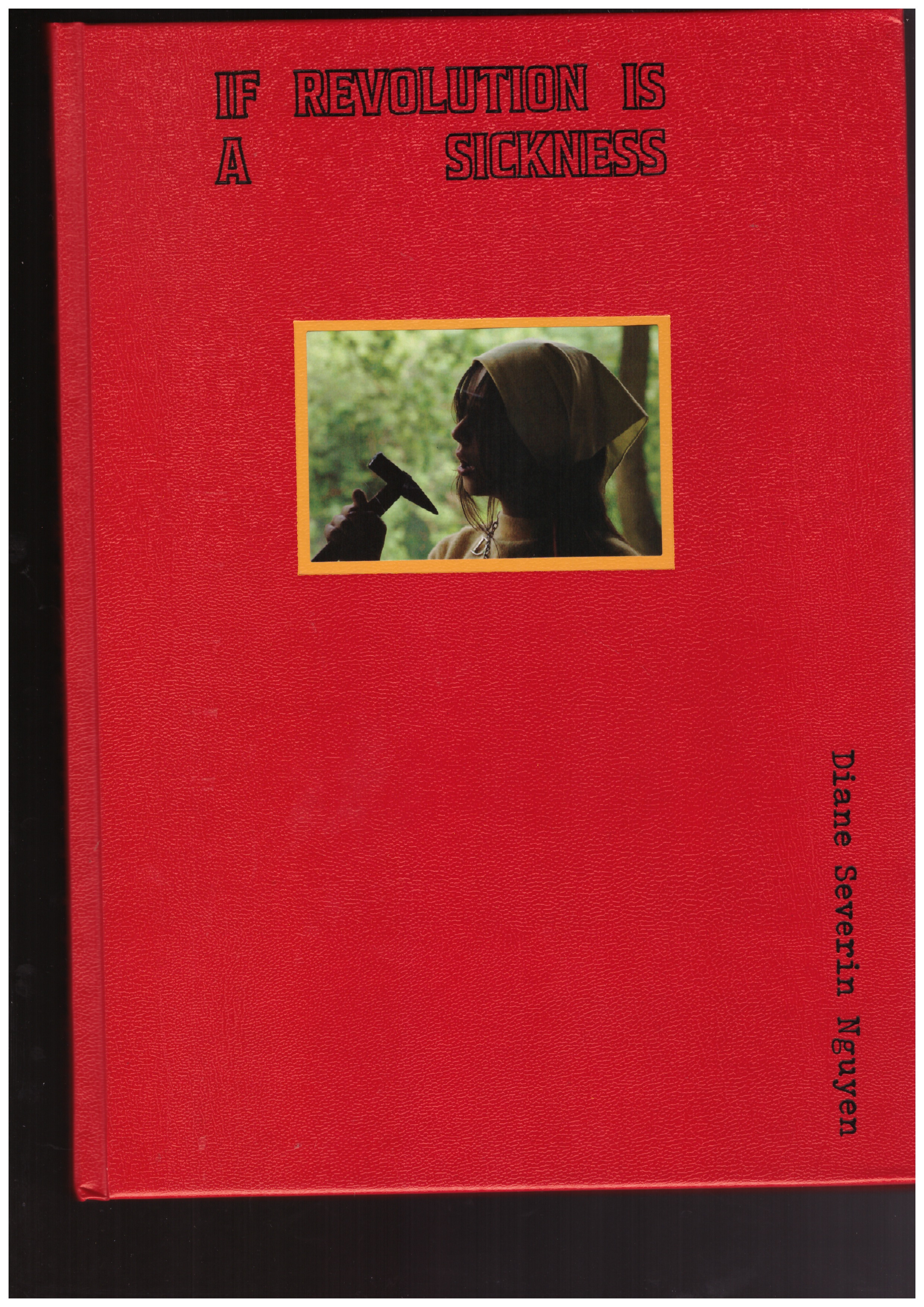

If Revolution is a Sickness

The first monograph on Diane Severin Nguyen’s work – that considers how songs and shared histories are woven together across different times and places.

If Revolution is a Sickness centers on a new film by Nguyen; set in Warsaw, Poland, and it loosely follows the character of an orphaned Vietnamese child who grows up to join a South Korean pop-inspired dance group. Popular within a subculture of Polish youth, the genre of K-pop is used by Nguyen as a vernacular structure as she traces a relationship between Eastern Europe and Asia that has roots in Cold War allegiances.

In addition to extensive imagery from the film and behind-the-scenes footage, the book also features essays by Cat Zhang on K-pop’s online communities and by Nathanäel on music, history, and geography; a pair of reflections on the film by curators Myriam Ben Salah and Sohrab Mohebbi; and a conversation between the artist and psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster. Also included with the book is a flexi-disc record featuring a song with music and lyrics co-written by Nguyen [publisher's note]

If Revolution is a Sickness was published in relation with the exhibitions of the works at SculptureCenter in New York and the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago.

Published by The Renaissance Society, 2024

Monographs